Welcome back! It’s the long overdue return of the Sudo Science Book Club! In this series of posts, I take a deep dive into books that resonated with me and simultaneously break down what I’ve learned and implemented from them. For the previous posts in the Sudo Science Book Club, see the further reading section at the end of this post. In the meantime, today’s Sudo Science Book Club, for the first time ever, will analyze two books for the price of one.

Just Tell Me How to Gamify The 12 Week Year!

I understand if you just want to get to that part. If you’re just here to see how I gamified The 12 Week Year, you can skip to the section titled HOW I GAMIFIED THE 12 WEEK YEAR (in BLUE ALL CAPS so you have an easier time finding it), because the following is going to be some background followed by an overview of my biggest takeaways from both books.

This past winter, two books popped up on my radar: The 12 Week Year by Brian P. Moran and Michael Lennington, and Actionable Gamification by Yu-kai Chou. It was difficult to dedicate myself to which book I wanted to read first, as both books looked interesting to me.

So what did Mr. Hyde decide to do? Juggle the two at once, of course!

Joking aside, stumbling across both books at roughly the same time was rather serendipitous, as I had just thought again about an old video from one of my favorite YouTube channels of all time, Better Than Yesterday.

I’ve been subscribed to his channel for years, but upon seeing this video for the first time years back, I didn’t find it appealing. Don’t get me wrong; I actually do like the idea of “gamifying” my life, being able to turn my productivity into something as addictive and fun as a video game. Why did I react the opposite way to this video from a YouTube channel I like so much?

In short, I had already attempted once in the past to turn my life into a game back in 2017. I’ll delve into details, but in a nutshell, I once used three or four Baron Fig notebooks and a handful of my favorite Blackwing pencils to gamify my life. I did this alongside something that was more like bog-standard daily journaling than the bullet journaling I prefer to do these days.

However, my setup was fundamentally flawed. I hadn’t realized how or why until years later. Yes, it all occurred to me as I read through Actionable Gamification. Reading through a good amount of it, I’m only more surprised I hadn’t given up on my old attempt sooner. I didn’t make my old system anywhere near entertaining, gratifying, or rewarding enough to keep going with. When my life had taken a huge turn at some point a few years later, I dropped it entirely and had nearly forgotten all about it. It was a true testament to how poorly-designed the whole thing was. Consequently, I nearly forgot all about it until reading through both of the aforementioned books.

On another note, one of those books is The 12 Week Year, which opened my eyes on why I found the concept of New Year’s resolutions so useless. I had been even more dismissive of the idea for most of my life without being able to adequately explain how or why until I read through this book. The book goes into more depth (I’ll elaborate on it all soon) on why “annualized thinking” is a worthless waste of time.

Still, the book proposes setting goals in a 12-week span for many beneficial reasons over setting yearly goals. It includes everything you need to get started with such a thing, and it is honestly a fully-contained system. For most people, it would be enough to read just this book and get started accomplishing your goals.

But despite that, I think recalling my failed attempts to “gamify” my life and stumbling across both of these books at the same time was destiny. I would go as far as saying that this has given birth to what might be one of the best ideas I’ve ever had:

What if I took the 12 Week Year system and turned it into a game?

Gamifying My Productivity

I read through both books, but had the idea to take notes on both during my reading sessions. Eventually, I started piecing together what I wanted to accomplish. I read The 12 Week Year in its entirety first, but by the time I was finished reading Actionable Gamification, I was already able to get a system up and running. Before I can simply describe my system, I think it makes sense to explain my biggest takeaways from both books first. Still, before I begin, don’t expect a total summary of everything I read. This is supposed to be my most useful takeaways that helped me piece together my system.

My Biggest Takeaways From The 12 Week Year

I got a digital copy of the book to read, so I can’t say how large the book feels in the hand. However, it felt short and engaging. If you happen to read through it for the same reasons I did, I would recommend skipping any of the paragraphs that bring up how to use the system in a team setting (unless that’s relevant to you, of course). These are parts of the book that mostly target people implementing the system in the workplace, usually as a manager or team leader of some sort. Since I am neither of those, I glazed past those parts and exclusively applied the methodology to myself.

Additionally, the final chapter urges readers to use the system as a whole instead of merely dabbling here and there. As a result, I tried my best to integrate as much as I could into my gamified setup. That said, what are some of the insights I picked up from The 12 Week Year?

Annualized Thinking Is A Waste of Time. Period.

You probably know at least one person who feels optimism around the last weeks of December. He’s probably thinking that a new year brings new possibilities, so he sets a goal, maybe a handful of goals. He’s thinking of the common resolutions, go-to goals like doing better financially, getting in better shape, or finally finding a hot girlfriend.

Fast forward slightly to see some effort at best and none at worst. For example, if he’s trying to get in better shape, he probably went to the gym on January 1st and 2nd, overdid it a little, and never went back, forgetting to cancel his gym membership for the following months. For the other goals, he makes even less effort, continuing to live paycheck-to-paycheck, racking up credit card debt, talking to no women whatsoever, and paying zero attention to his appearance.

How does this guy react? Maybe he lashes out at others, maybe he blames factors outside of his control to make himself feel better. If he’s a normal person, he might just quietly forget, maybe feeling slightly guilty at times, until later in the year. The 12 Week Year proposes this scenario, but with said person realizing it’s already late November and saying, “Oh! It’s November! I need to get to work! I only have a few weeks left,” only to fall short by the end of December.

But I think we all know what would really happen. Instead, he’ll notice it’s November and dismissively say “Hey, I failed my resolutions! Oh, well!” to himself before planning the same resolutions again in late December. Rinse and repeat another 12 months later.

The book proposes setting a 12 week deadline for accomplishing goals because it’s long enough to get big tasks done, but short enough to feel urgent compared to an whole year. If someone with New Year’s resolutions waits until March, he’s likely to tell himself, “Whatever, I still got nine whole months left,” which leads to further inaction and procrastination.

The book cites a company going through the motions until the final few weeks of the financial quarter, only to suddenly amp everything up and do exceedingly well just to meet expectations for the fiscal year. That begs the question: Why not have the same kind of high-level performance the whole fiscal year instead of just in a short period of time? Why not have the same high performance in achieving our goals instead of waiting until we only have a little time left?

By reducing the amount of time to a shorter period, treating 12 weeks as if it were one year, we can give ourselves much-needed urgency we would otherwise lack. As another benefit, we can treat a calendar year as four years within The 12 Week Year system, which means we have more time to get more goals done than someone still subscribing to annualized thinking. Still, this isn’t enough to get our goals done, which leads me to my next point.

Knowledge Is Nothing Without Execution

Going back to the previous example about the guy setting New Year’s resolutions, we can focus on how he wants to get in better shape. If I were to talk to the guy about how to lose weight and build muscle, he’d likely say the same things most, if not all, of us know.

“You gotta work out regularly,” “You need to eat less fast food,” or “You should add more protein and vegetables to your diet.” He knows all of these things; more importantly, he knows he could just do these things. How far has that gotten him? Having the knowledge is useless without a plan to execute any of it.

The 12 Week Year proposes something that makes an insane amount of sense: People have an execution problem. We have the knowledge we need, but we just need to apply it, to execute it. This book solves the issue by detailing ways to help readers plan and execute goals more effectively with clear and measurable goals.

Multitasking Is Dumb

So many people won’t admit it, but they multitask. In our attempts to get so many things done at the same time, we do the exact opposite without even trying!

This has been studied outside the book, but humans are not built for true multitasking outside of a gifted 1% of the population. For one to instantly assume he or she is part of this minuscule 1% is the Dunning-Kruger effect in action. It’s this 1% that can not only multitask, but do it extremely effectively, completing two or more involved cognitive tasks at once while making it look effortless.

If you’re a mere mortal like myself, here’s how we really “multitask” when we try: We switch from one task to another repeatedly, making ourselves less focused and effective as we go along. There’s an “attention residue” that builds up and causes us to take longer to get back to concentrating fully on the task than if we had simply worked on each task separately.

While the book doesn’t discuss this in too much detail, it does point out that multitasking is ineffective at helping us achieve goals. If we attempt to multitask, nothing will ever get our full, undivided attention.

The book cites the idea of a world class athlete winning a gold medal because he put effort into training for months or years into his event. However, most people think the greatness is affirmed right there at that event. In reality, the athlete has focused his full attention on training for so long that the event does not. Rather, it reconfirms what he has already worked on. He built his greatness over time with each rep, crunch, squat, lift, or run. By being able to fully focus on training, he builds his greatness with each exercise, each individual effort as it adds up. Greatness is born in the moment as he focuses his attention on his workouts.

Even those who mistake the gold medal as the moment of the athlete’s greatness may mistake each individual effort or workout as no real presence of greatness. They simply think it’s being mediocre on one’s long path to greatness, and that’s usually because they can’t see the results come quickly enough. A massive takeaway from the book is how the key difference between greatness and mediocrity on an immediate basis is narrow, but the difference months or years down the line is immense.

Intentional Imbalance Will Get You There Faster

This is something I was personally guilty of for years as I attempted to achieve my goals. Many times in the past, I set multiple goals at once, which isn’t a bad thing. What was bad, however, was my attempt to juggle all of them with mostly even effort spread across all of them.

Trying to spend an equal amount of time on every area in one’s life is a frustrating and unproductive mistake.

The 12 Week Year instead advocates for intentionally choosing to imbalance one’s goals. It sounds so counter-intuitive, but it’s comparable to why multitasking doesn’t work. Picking one specific area or goal to divert more effort and energy can lead to results much faster. Instead of nebulous notion of simply “trying to get better” at a goal, the book proposes an approach in this style during your 12 weeks:

- Come up with a list of actions (or “tactics”) that can make the goal possible, then follow through with all of them. Most of all, make sure they’re specific, doable, and measurable. For example, a fitness goal in 12 weeks might include 20 minutes of cardio 3 times a week, training with weights 3 times per week, drinking 6 glasses of water a day, and so on.

- Identify a “keystone,” or core action, to focus on during a 12 week span. For instance, if a guy is trying to improve his marriage with his wife, he might want to plan one date night each week for the next 12 weeks.

Again, a lot of this is starting to look familiar because it reads a lot like the “implementation intentions” from James Clear’s Atomic Habits. I already stumbled across this recurring idea when I recalled my biggest takeaways from The Bullet Journal Method by Ryder Carroll. Still, it’s another useful parallel because they are clearly-defined tasks that are planned at specific and measurable intervals.

Make Your Actions Measurable and Goals Doable

I don’t know how many of my readers will remember watching Ned’s Declassified School Survival Guide way back in the day, but I recall an episode where the titular character set a goal to “do better in science class” along with several others.

I’m hard-pressed to remember the other goals, but I specifically remember this one because of how he “accomplished” it. In the episode, Ned enters his science class, glances at the periodic table, comments on an element he didn’t know before, and scratches the goal off his list.

When confronted on this, Ned argues that it was one more element from the periodic table than he knew last year, so technically, he was already doing better in science class.

This goal would have been much better for Ned had something measurable and doable to repeat. For instance, if a student like him had planned “get at least a B+ final average” as his goal, that would have been measurable. He could have had tactics like “study science textbook twice this week,” or “read an article from 3 science magazines per week” to help him get the ball rolling.

I mention this because vague, hard-to-measure goals can hurt more than they help. Going back to the guy I mentioned at the start with his New Year’s resolutions and annualized thinking, his fitness goals and actions likely would have been vague or hard to approach like “lose weight,” “get in better shape,” or even “run a marathon.”

Okay, the last one is measurable, but how is he supposed to build his way up to running a marathon, especially if he’s a couch potato with zero running experience? Someone in his position can pick a goal that is measurable but not doable only to set himself up for disappointment and failure. Much like his attempts to hit the gym daily until January 3rd, he’ll most likely go out to run only to feel exhausted and out of breath after ten minutes, wondering if he’s even remotely close to running a half-marathon. The goal would seem too far away, and he’d most likely give up.

To achieve this goal, he needs something not only measurable, but doable. He could look into a Couch to 5K plan, start with it, work his way up to a 10K, work up to a half-marathon, and eventually train for the full marathon itself. This would work marvelously because these are measurable running distances to strive towards.

Measurable goals and doable actions can help us effectively and clearly plan in order to improve much faster.

There’s A Better Way to Time Block!

I have already discussed time blocking before. However, I liked what The 12 Week Year proposed as a type of time blocking that is more attuned with achieving one’s goals in this system.

In short, there are three types of blocks to use each week:

- Buffer Blocks are normally blocks you can set up for short periods like 30 to 45 minutes a day on a frequent basis. The idea is to schedule these chunks of contingency time in order to deal with miscellaneous tasks that aren’t directly connected to your goals. This means handling company emails, filling out reports, answering some phone calls, and other things that might otherwise add up. By dealing with these smaller interruptions in dedicated chunks of time, we become less stressed down the line. Less stress later means more time and energy to complete tactics and achieve our goals.

- Tactical Blocks are longer, usually an hour or two. Schedule a few of these a week and dedicate said time to completing smaller tactics. They’re all about making execution happen. The book only recommended one, but I like having at least three per week to see how much action I can cram into a given block of time.

- Strategic Blocks are usually at the end of the week. They’re about reviewing your progress, planning ahead, and anything that gets the needle moving on your long-term goals as a whole. I typically make these two hours long.

Since incorporating these into my existing time block setup with whatever I’m using as a calendar, I’ve felt myself making more progress on my goals.

The Emotional Cycle of Change is REAL

This was something touched upon in The 5 AM Club by Robin Sharma that I didn’t emphasize, but there’s the idea that a major, positive change can “scare” our minds into giving up if we venture too far into it. Despite how accurate that is, it offers little in real advice on how to overcome that, instead urging you to persist with little more than motivational words. It only offered lofty promises of how greatness lies ahead if you just keep going.

However, The 12 Week Year has a much better explanation of how this phenomena works and, subsequently, how to overcome it. The book calls this the “Emotional Cycle of Change,” or ECoC as it is abbreviated as in subsequent chapters. This describes the feeling of most people as they attempt to embark on making a major change for the better in their lives.

In short, whenever we start trying to make positive changes in our lives, we embark on this cycle whether we realize it or not. In the beginning, we are in stage 1, uninformed optimism. This is when we daydream and plan how much better everything is going to get when we start making changes and achieving our goals. We’re planning for how everything will go, feeling excitement of all the possibilities waiting for us. As we continue, we enter stage 2, known as informed pessimism.

In this following stage, we start to feel some resistance because we’re making big changes. It usually is a result of realizing that meaningful self-improvement requires consistent effort and consistency on our part, perhaps more than we realized. Some part of our brains is terrified of this level of change as it continues, as we still aren’t used to our new routines and improvements.

If we’re not aware of it, we won’t know we’re heading into stage 3, the so-called “Valley of Despair.” Here, we hit our point of highest resistance, where many of us rationalize giving up. Going back to the guy with his New Year’s resolutions on fitness, this is when he starts thinking, “This is kind of hard. You know, my life wasn’t so crummy before. I was mostly happy before I tried to get in better shape. It’s not so bad being forty pounds overweight.”

If he fails to push forward, he gives up, regressing back to the same old habits that brought him where he started in the first place, unaware of what he could have done differently. That is, until he gets inspired enough to give it another go, which will have him looping stages 1 through 3 all over again.

Had he persisted, he would have seen improvement slowly over time, bringing him past the fourth stage of informed optimism. This is where he would start to see the fruits of his labor. All he would have to do is keep it up before coasting into stage 5 of achieving his goal, success and fulfillment.

An effective execution system also helps us reach stages 4 and 5 instead of repeating stages 1 through 3 ad nauseam. Without a specific and measurable system to keep us on track, we will inevitably fall back on our old habits, our old “systems,” merely because they are familiar.

Merely being aware of this cycle makes us less likely to give up on our goals. We’ll be able to see where we are when things feel difficult, reminding ourselves to keep going and to push past the Valley of Despair, our points of highest mental resistance.

Compatibility of the 12 Week Year System

This is something else I noticed while reading, but the whole system conceived in the book is designed to correct itself in case we veer off course from achieving our goals. It’s a self-contained system, in other words.

While the book simultaneously urges using as much of it as possible (as opposed to “dabbling” a little in one aspect or another) and to try applying it to other existing systems to prevent upheaval, this is when I came up with my idea.

There’s More?

As I said, I’m not here to merely summarize The 12 Week Year, as others have already done it before myself. I just wanted to highlight what I found important from the book. I’m not sponsored or paid to endorse the book, but I do think it’s worth a purchase and a read. Readers will find more specifics I didn’t even touch upon, such as the importance of our vision, the 5 disciplines, or specific steps to follow in order to get started from the beginning. The only way to really implement everything is to find out how all of it fits together.

However, I did want to stop this post from growing too long, as I wanted to describe how I implemented the system soon enough, although that leads me to the other book that inspired this entire system.

My Biggest Takeaways From Actionable Gamification

Thankfully, there’s a lot less for me to write about in this book. While I do think Yu-kai Chou’s book on adding “gamification” elements holds some valuable ideas, I do think it suffers from excessive padding. My used copy of the book was rather large at several hundreds of pages. After reading a good amount, there is so much that could be trimmed without losing the main point. Some chapters really stretch because we get multiple real-world examples of companies implementing something to “gamify” their business or customer base. Usually, we get other examples of the main idea from the chapter in action in some other context to further reinforce the idea.

After the long examples, we then see direct tips listed in said chapters (the best parts of the entire book because of how applicable they are), get immediate to-dos to help us apply what we just learned, and explore the next part of the “Octalysis Framework,” a diagram showing possible elements to gamify various parts of games, business, lives, or systems.

The book introduces this idea early on, but, confusingly enough, starts to fill out parts of the Octalysis Framework diagram with various other games that were popular circa 2015 or before. Keep in mind it does this before explaining what any of these parts of the core even mean. This results in readers, like myself, having to thumb back to these pages after reading most of the book to see how everything fits into place.

In terms of other drawbacks, a few parts of the book could stand to be updated, as it feels somewhat like a time capsule from 2015. If it has been, I must have gotten the first edition. It mentions how Candy Crush Saga has made big strides in engaging users as if it’s still culturally relevant, it brings up how Zynga uses “black hat” (read: darker or more malicious) gamification techniques, as if they’re still a huge company. The book even naively suggests tracking aspects of our lives using smart devices and Big Tech.

As a result of this and a few other issues, I dropped the book after reading around 200 pages in order through it. It was after this point that I started to skim ahead and cherry pick the most useful information. Thankfully, despite it not being as cohesive or “tight” of a read as The 12 Week Year, I did take a lot of good from Actionable Gamification.

Points, Badges, and Leaderboards Only Go So Far

Early on in the book, we are introduced to the idea of “gamifying” our lives and work, how keeping score makes things more exciting. However, Chou also describes how it can be done poorly. Many companies, looking to drive more engagement, just think to themselves, “People like games, right? Why not throw some game-related stuff in there! It’ll be just like playing a real game and they’ll automatically like it more.”

In reality, when this attempt to gamify something is done with such shallow contempt, it results in users or customers feeling alienated, possibly even insulted. There are right and wrong ways to add game elements to things that aren’t usually games, and the Octalysis Framework gives a great, well, framework to do just that.

Combining Some Parts of the Octalysis Framework Can Be More Effective

Looking back at the diagram, It makes sense to briefly explain the eight parts of the framework.

- Epic Meaning and Calling – Engaging players or users with the idea that they’re part of something greater than themselves.

- Accomplishment – Making players or users feel like they earned and accomplished something can increase engagement.

- Creativity and Feedback – Finding ways to let players get instant or near-instant feedback on their creativity and thinking will drive engagement.

- Ownership – Giving players or users control over something they feel is rightfully theirs can increase “buy-in,” a sense of investment.

- Social Influence – Allowing players to connect with others and belong in a community of other likeminded players.

- Scarcity and Impatience – Using the idea of FOMO and limited availability to drive more urgency and action from users or players.

- Unpredictability – Using mystery or randomness to drive the user or player’s curiosity in order to keep everyone coming back to engage more.

- Loss and Avoidance – A desire for players, already having invested so much time and energy, to work towards not losing what they have.

Some of the games we play (or even businesses we engage with) tend to use some of these elements to make it more compelling to come back. I can’t exactly see any single game using all of them, but many do use a good handful in tandem with one another.

Why My Old Attempts to Gamify Failed

Despite its issues, Actionable Gamification at least shed light upon why my old system from 2017 fell flat.

With my old system, I attempted to make my life like an RPG where I gained XP and leveled up. I had been largely inspired by an app that did the same thing just a year or two prior, but I didn’t want to pay for its premium features. That’s when I thought I could just do it myself.

I implemented a list of actions that caused me to gain or lose XP, and I would just level up with a linear calculation of 1000 XP per level.

However, after reading through enough of Actionable Gamification, it soon dawned on me why my system failed after a few months.

- I only had a straight line to move in with leveling up. I just collected XP and waited until hitting a new level. That was it.

- My actions were difficult to keep track of. I had to thumb back to specific pages to see what XP I would lose or gain, and it was largely inconvenient.

- Some of my actions were less focused on a long-term vision of making myself better and instead focused on consumption. Right now, the only media I really try to focus on consuming more in my system is books, but my old system tried to grant XP for playing video games and watching more shows or movies that were on my endless backlogs.

- If I hadn’t accounted for a desirable action to add to the list and still completed it, what was I supposed to do? How much XP did it need to count as?

- There were no rewards in my system. Huge mistake. What would keep me coming back to do better?

- I had no easy way to keep track of how well or poorly I had done without opening my A5 notebooks to check my master lists of actions.

The whole thing became a pointless exercise of watching a number go up and hoping I could make it go up faster. That only got me so far, especially as I learned about the Octalysis Framework, which did give me valuable insight on what could have made this better.

HOW I GAMIFIED THE 12 WEEK YEAR

That said, I decided years later to gamify the 12 Week Year system. Learning from my past mistakes, I planned everything out differently this time around.

I was going to take as much as possible from the 12 Week Year system. As the book said, don’t just use a small amount, but almost everything (barring the parts on applying it to my business). I chose to avoid merely “dabbling” with just a small part here or there and hoping it would all work in isolation.

Considering what the 12 Week Year said, it could also be used to prop up an existing system, to further support or reinforce it, which was why I was very deliberate with this in mind.

So how did I do it? Let’s start with how I tracked everything first.

Tracking With Digital and Analog

I wanted everything to keep track of to be much easier to find and reference than before. No having to hunt through pages of my old Baron Fig notebooks. Instead, this was a great chance to have my second brain (now supercharged with Zettelkasten) serve me further.

However, I’m still a bit of an analog nerd, so I wrote down my overall progress on a notebook I had lying around, a Rollbahn spiral notebook my girlfriend gave me for Christmas.

Setting Up Specialties to Work On

I wrote lists of actions, or “tactics” as The 12 Week Year would call them, and categorized them by “specialty” like parts of a skill tree of sorts.

As an example, my current specialties of focus are “Fitness,” “Home,” “Reading,” “Finance,” “Writing,” “Work,” “Language Study,” and “Music.” These more static parts, my set lists of specialties and tactics, would be in my second brain, while I would record my progress on paper in my Rollbahn each day.

Key word is also “more” in “more static,” as in somewhat dynamic. If I feel like something should be worth more or less XP, I can always go back into my second brain to make adjustments or add new tactics without the fear of running out of space on a paper or having to rewrite everything on a new page in another notebook. I can also reorder everything by XP amounts rewarded or alphabetically by task. To keep track of changes, I have a separate note set aside for “Patch Notes” (including version numbers) in order to keep with the video game theme.

Deciding How Much XP For Actions and Goals

I assigned XP amounts to various actions and tactics depending on how little or how much I wanted to do them. If they were simple things I liked actively doing, I gave myself less XP for them. If they were things I would procrastinate on often, I gave myself additional incentive by making them worth more XP overall. Conversely, there are no penalty systems in place, unlike my old system. I don’t have a list of activities to avoid that cause me to lose XP.

To keep myself pushing harder, I wrote down a list of loftier, bigger goals worth immense amounts of XP in a separate list. I split them by category, calling them “boss battles” to keep up with the gamification theme.

Turning 12 Weeks Into An In-Game Season

I turned each of the 12-week periods into “seasons” like that of a live service game. As much as I despise live service games as a whole, this is something that feels much more useful to take inspiration from here.

Each “season” has a different theme for me to focus on, hence my “intentional imbalance” from The 12 Week Year. For instance, Season 1 of my system is centered around fitness. While I still get XP for doing other productive things in my life, I get a 1.2 multiplier bonus (keeping in tune with the theme of 12 Weeks) for anything fitness or nutrition-related that I complete in a given day. As a result, I have a direct incentive to focus more on working out or exercising than I do practicing guitar or learning another language. That is, until my season ends and the next one starts, focusing on a new area that gets the 1.2 multiplier bonus.

Weekly Battle Passes (Yes, I Went There)

I harnessed the power of measurable tactics each week in The 12 Week Year with “weekly battle passes.” I use my strategic block each week to plan a battle pass by hand-picking a series of tactics I want to focus on. On top of said tactics granting slightly more XP, I make it so that I complete each tactic around three times in a week, although some may be more frequent (easier tactics) or less frequent (difficult tactics or “boss battle” goals).

To get myself to really want to finish a battle pass, XP rewards are multiplied more. Every tactic in a weekly battle pass goes through a 1.4 multiplier bonus, and that’s on top of the 1.2 multiplier bonus for tactics that my season is focused on. For example, if my season is focused on fitness, any actions I take toward my fitness goals normally give me a 1.2 multiplier bonus. If these actions happen to be in a battle pass, I multiply by 1.2 first, then I multiply that result by 1.4 to really compound my interest.

By completing a battle pass 100%, I can unlock a giant XP bonus on top of finishing it, further granting incentive to complete it before the week ends.

Once the week is over, I use part of my strategic block to review how everything went that week. I’ll review my tactics for the week and see how I did overall, calculating and giving myself a completion percentage. I only unlock the biggest XP bonus by going to 100%, so it becomes an all-or-nothing affair if I want to level up faster.

What happens if I complete a battle pass before the week is up? This is another place where the system really shines. After completing a pass, I don’t have to wait for a new week for a new battle pass to begin! Instead, I can start next week’s battle pass with a double XP multiplier bonus for finishing the previous one early.

For any goals related to my season that normally get the 1.2 bonus within the battle pass, I first multiply by 1.2 and then double the amount of XP in that order. To keep everything balanced and stop the battle passes from being too strong, this double XP bonus only lasts before the scheduled start date of the battle pass, so it rewards me for taking enough extra initiative to get started instead of sitting around.

Level Up Calculation With An ln Equation

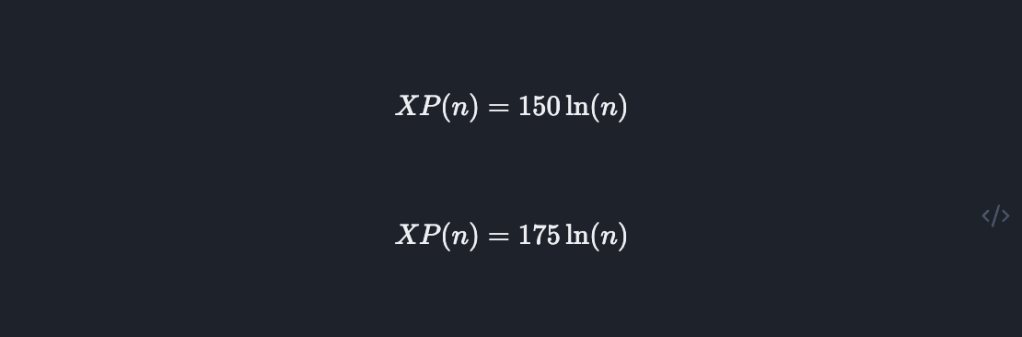

To calculate how I level up with the XP, I no longer use a linear calculation of previous level plus X amount of XP. Instead, I consulted someone close to me, someone well-versed in calculus and mathematics for her job career. She eventually helped me narrow my scope to the following ln equations:

In this equation, XP is calculated by plugging in n, which equals the given level. I set everything up so that my 1st level requires 0 XP to begin on it, so I would plug in n = 2 to calculate how much I need to advance to level 2.

I switched from the first one, with a constant (read: this number stays the same each level) of 150, to the latter equation with a constant of 175 once I advanced past level 20. I thought this would provide a bit more of a challenge with slightly slower leveling without it becoming an insurmountable grind.

Calculating all of this was much easier with a graphing calculator I held onto for a few years. I plugged the equation in and checked the table function to see what value every level would be in a straight line. To account for decimals after using the equations or using the multipliers (it happens), I simply round up if the number after the decimal is higher than 4. I round down otherwise.

I took these amounts and accumulated them with the previous levels. In other words, to get to level 3, I have to accumulate a total XP amount that’s equal to what I get from the equation for level 3 plus what I already have saved up from previous levels.

Reward Milestones and Unlocks

To keep myself going, I have a list of rewards I unlock every 5 levels, so at level 5, 10, 15, and so forth. I don’t unlock these in a linear fashion where one rewards is set at level 5, and another is already predetermined at level 10. To keep things interesting, I created a few tables in Obsidian listing 12 of the rewards each, to keep with the whole “12 Week Year” theme.

Each reward is labeled with a column showing numbers 1 through 12. When I hit a milestone every 5 levels, I roll a 12-sided die and see what number it lands on. I match that number with one on the table to see what reward I unlock. If it lands on a number for a reward I already redeemed, I simply roll again. This adds a sense of unpredictability that makes the system more compelling than if I had preset reward unlocking. Another column next to the rewards shows the status of that reward as “Pending,” “Deferred,” or “Redeemed” to help me keep track.

Carefully Picking Rewards

Picking rewards can be difficult, and YMMV. For instance, if my focus during a given season is fitness, it isn’t the best plan to make most or all of my rewards involve indulging in fast food, candy, ice cream, or 12-packs of beer. If my focus is finance with specific goals to save money and keep a budget, my rewards shouldn’t be a laundry list of expensive trinkets I don’t need that lose their luster after a few days.

In other words, be thoughtful and reasonable when it comes to rewards. You can let yourself indulge a bit, but don’t overdo it. I had a reward that was a tall can of beer, and that’s fine compared to enjoying an entire 6 or 12-pack in one sitting. Be sure to pick rewards that excite you enough to earn them without having them harm your goals.

Categorizing Rewards By Magnitude

This is another strategy I stumbled upon when experimenting with the rewards (see the note and update further below about my pre-order). In short, I set a special milestone to hit a specific level by a specific date, allowing myself to make a major purchase on something if I could do it fast enough.

The only real way to level up fast enough was to complete my battle passes as much as possible, and those align with my intentional imbalance and season-focused goals. After realizing how successful I was with this goal while being able to lift heavier weights than two months ago, I decided to expand a list of loftier, more expensive rewards for every 50 levels.

However, each one has a set deadline in the future. I’m still experimenting with length, but I like the idea of 6 weeks (midway through a given season) being the deadline for these bigger rewards, as they also spare my wallet from being hit too hard with the possible cost of these rewards.

Crunching Numbers With My Save Point

At the end of the day (and I mean that literally, as in 8:00 PM), I begin my “save point.” This is where I open my aforementioned Rollbahn notebook and start recording what I did in a given day, cross referencing my tactics lists to write down how much XP I’ve earned.

I used to do more elaborate stuff to make everything feel more video game-themed, but I eventually stopped because it saved time to simply calculate everything instead. If somebody really likes the ornate side of bullet journaling with Pinterest-like layouts, I can see somebody wanting to draw and color elaborate meters and bars all over the page with sprite art, but that’s not necessary for my needs.

I use a bullet journal-type of format to add up points where the left margin has a number on the side denoting the amount of XP for the tactic I completed.

I put parenthesis around numbers to denote any possible multipliers, whether it’s for a season-centered tactic, a battle pass action, or both. If it’s both, I use double parenthesis so I won’t forget to calculate the multipliers correctly.

How Is It Working So Far?

In all honesty, I’ve been test driving this whole thing since late December, specifically the last three days of 2024. However, I scheduled season 1 to start on New Year’s Day 2025, but to encourage myself to start earlier (and discourage annualized thinking), I called that span of a few days my “open beta,” granting myself a double XP bonus on any productive tactics I completed until New Year’s Eve. As much as I detest actual live service games, I do like applying its theming and ideas to my system.

Fast forward to now, and I’ve been almost 100% consistent with it. I only took a short break from it in early February when I came down with the flu for two days. Once I was well again, I wrote a contingency list of tactics to complete when I become sick so that I can still feel productive trying to get well again.

To give myself a little more encouragement, I started to create my monthly spreads in my bullet journal to account for my leveling up. Alongside events or experiences each calendar day (think of the plain spread that Ryder Carroll would use), I now have dedicated columns showing my current amount of XP and my current level in my gamified 12 Week Year system. It’s really something else to glance at my bullet journal monthly spread and see the before and after of what level I started off on versus what level I finished the month on. It gives me a visual sense of growth that I can actually see on paper.

To make things more interesting, there is something I would like to buy this month, so I made it a milestone reward to complete by mid-March. I did this because it’s a pre-order for a product I find exciting (I might write about it should I get it), and waiting anytime past the specified date means I’ll have to pay more to get it later on rather than paying less and getting it sooner. I’ll update this post later on regarding whether or not I was able to unlock the reward and make the purchase after all.

UPDATE: I DID IT! I actually hit my milestone and unlocked the reward with a day to spare. I’ll gladly report back on the product in a future post, but for now, it’s going to be an upcoming surprise.

How I Applied Gamification As a Whole

If I’m going by the Octalysis Framework conceived by Yu-kai Chou, I made the 12 Week Year system stronger by incorporating more of these elements:

- Accomplishment, because seeing my progress continue makes me feel accomplished. Unlocking the rewards feels, well, rewarding, giving me the sense that I’ve genuinely earned them.

- Creativity and feedback, specifically as I complete an action knowing full well that it will grant me XP that I can add up for my save point later in the evening.

- Ownership, because it’s an entire system I’ve created myself, applying what I’ve learned from reading through both books and taking notes.

- Scarcity and influence, because battle passes only last a week. I have to complete them 100% to earn the most XP possible. Same with the new reward I set up for myself by mid-March, which further increased my urgency.

- Unpredictability, specifically in my rewards system. Instead of knowing what I will definitely unlock each five levels in a predetermined setup, I have to roll a 12-sided die to see what I get when I reach the milestone.

I know there are some cores I didn’t use, but not every core has to be used to make a game fun and engaging. They’re akin to spices in food, where using all of them just because you can doesn’t make the taste much better. Just so long as the combination of cores makes sense for the given experience, it should be enough.

What Have I Learned?

In short, here’s everything I’ve learned from reading both books and setting this whole system up.

- Annualized thinking is pointless. The sooner we abandon it, the better.

- Knowledge is worthless without a plan to apply, to execute, what we’ve learned.

- Multitasking is counterproductive and can hurt our productivity in the long run.

- Sometimes, we have to intentionally imbalance our goals to achieve them faster. This is a lot like a form of single tasking.

- Actions, tactics, and goals should be measurable, not vague. Otherwise, we’re far more likely to give up on them because we won’t be able to see our progress.

- Time blocking can be more effective if we have specific types of blocks (buffer, tactical, and strategic) to help us inch closer to our goals.

- The Emotional Cycle of Change is very real, and it’s a huge reason so many people fail to achieve productivity goals. Becoming aware of it gives us greater chances to move past the “Valley of Despair” and attain greatness.

- The 12 Week Year is a closed system that encourages using as much of it as possible, but that doesn’t make it incompatible with other systems. It should still work as long as we’re not merely “dabbling.”

- There are main aspects of “gamifying” our lives and work, these “core drives” in the Octalysis Framework. Knowing how to synthesize them together can make any game or gamified idea much stronger.

- My old attempts to gamify my life failed miserably because I was completely unaware of the ideas in the Octalysis Framework. Had I known about them, I would have been able to design a much smarter system.

Leveling Up From Here

Have you ever heard about The 12 Week Year before reading this post? What is your opinion of annualized thinking after this? Have you ever gamified any aspects of your life before? If so, how did that turn out? Do you have any other thoughts about the system I’ve created? Maybe you can think of something else I can add to it, or some other way I can further improve it. If so, feel free to leave a comment. I’d love to read what you have to say on this.

Further Reading

8 Great Lessons from The Bullet Journal Method

5 responses to “How I Turned The 12 Week Year Into a Game”

[…] just Manjaro on a Windows-hosted VM. Mike is also a Peter Griffin-looking guy I talked about in my 12 Week Year book club post who annually gives up on all of his fitness goals by January 3rd because he’s always too busy […]

LikeLike

[…] example deals with my attempts to gamify The 12 Week Year, which I started back in late December. However, I was having issues for the past two week trying […]

LikeLike

[…] hinted at it way back when I first started writing about how I turned “The 12 Week Year” into a game, but it’s easy to forget since it has been a long time. In short, I mentioned setting up a […]

LikeLike

[…] neglected music collection properly. In fact, during some downtime at home, when I wasn’t trying to earn XP in my gamified self-improvement system, I would go through my library and start updating tags […]

LikeLike

[…] archive names and physical descriptions to help me dig them up faster) as well as my now-simplified life gamification setup (which I really should update on sometime). I also keep a handful of old notebook pages in here […]

LikeLike