It’s no secret that I’ve been exploring Arch, Fedora, and openSUSE for the past few years. While I did use Ubuntu back in the late-2000s, I only used Kubuntu briefly before really going all-in on Arch during the lockdown a few years ago. Still, the point is that I have experience with the aforementioned list of distros at the start, and I’ve gotten through a few different setups and workflows. From simply trying to recreate the macOS workflow with Latte dock and global menus on KDE to switching to my first tiling window manager, I’ve tried a lot of different desktop environments and a few window managers.

As a result, I thought it would be fun to follow up my top 3 Linux color schemes blog post from a while back with my top 3 window managers I’ve used. Granted, I have used a good handful of window managers, but these three are the ones I’ve been able to use for a good amount of time. However, that’s not to say that I think an excluded window manager is bad or not worth using. Rather, if you have another idea for a WM I didn’t include, it’s likely because I haven’t used it for long enough, if at all. Unlike a few people out there, I don’t really WM-hop for the most part.

Why Use a Tiling Window Manager At All?

The funny part is back when I started my Linux journey that I didn’t see much of a point in using tiling windows at all. I was used to the floating window workflow from years of using Windows and macOS, and it didn’t really make sense for me to change what I thought was good enough at that point. Why bother switching at all if things are already good enough?

That was when I saw a video from DistroTube on the subject several years ago.

Before seeing the video, I was unaware that anybody out there had even been trying to “discredit” tiling window managers in the first place. In all actuality, I did see tiling window managers in some screenshots here and there, but I thought they just looked a bit complicated or hard to set up, and I didn’t really think much of them beyond that as I went back to my KDE or Cinnamon setup.

However, after watching the video, I found DT’s points extremely persuasive to the point where I was willing to give a window manager an actual shot. Before I knew it, I searched up a video he made configuring a different window manager (more on which later) and found myself falling in love with the workflow, the shortcuts, and all of the other little efficient quality-of-life improvements that come from a tiling window manager’s setup.

Since then, I haven’t really been able to use a desktop environment without some form of tiling windows. I can’t use GNOME without Forge anymore, and I couldn’t use KDE without Bismuth (RIP Bismuth). I needed the tiling windows and felt less efficient with floating windows in my setup. In the handful of times I used a floating window desktop environment, I would find myself manually dragging the windows to cover up the whole screen in a setup similar to what I would have with a tiling window manager.

Honorable Mentions?

It’s a fair question to ask me if I even have honorable mentions at all, but I haven’t really used a lot of window managers as a whole. This list includes the WMs I didn’t handle for too long. Consequently, whether you want to count this short list as my honorable mentions will be left to your discretion. It’s possible I could come back to use these at a later date, but it’s not likely right now, as I do like the current setup I have right now with my number one choice on this list. The window managers I’ve tried and didn’t use for long are as follows:

- xmonad

- Qtile

- bspwm

DT always had a lot of nice things to say about xmonad, but I had such a difficult time trying to configure it for the longest time whenever I would try to go and use it. In hindsight from when I last used it around two or three years ago, I’m sure I was just doing something wrong. I had also attempted to learn some Haskell during the lockdown and found the idea of configuring a WM in Haskell a bit intimidating as well. I’m sure if I went back I would have a somewhat easier time getting things going.

Qtile is another one I didn’t spend too much time with. While I did find a good preconfigured setup to use with it randomly on a whim, I found it offered no serious advantages compared to another one of my top choices at the time. I do know that it is configured in Python, which could be a plus for anybody proficient in that programming language in particular.

Last of the other window managers I used was bspwm. I found this one a bit too minimal to my liking, and I didn’t like the idea of trying to configure or use polybar to make a usable setup with it at the time. I had also last attempted to use it on my laptop a couple years back and couldn’t get it to play nice with a HiDPI setup. In hindsight, I probably would know how to get it all working now if I gave it another shot, but I don’t really have much interest in doing so, although I could think of something else I could possibly do to get use from it at some point (more on that in this post soon).

That said, let’s finally take a look at my top 3 tiling window managers.

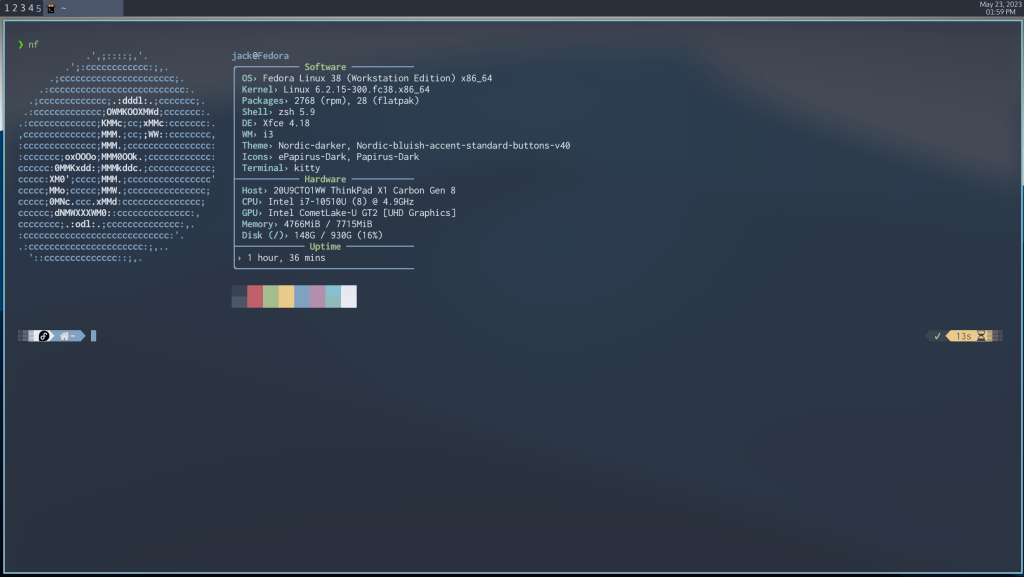

i3 Combined with a Lightweight Desktop Environment

Wait, does this count? It’s my list, and I argue it does. I played around with this idea in the past and had some mixed results with it, but I really like the idea of combining i3 with a lightweight DE such as XFCE or MATE. In the case of MATE, especially for people who used Ubuntu back in the GNOME 2 days, this can make something old and spartan feel extraordinarily new and modern.

In short, you install a desktop environment like XFCE or MATE, edit some dconf files to replace the default window manager within those desktops with i3, set up your i3 config, and then start the desktop environment to get the benefits of tiling windows. What I find so elegant about this setup is how it’s perfect for somebody who may be new to tiling window managers, somebody who may be curious about them but is daunted by the idea of setting up so many components for workspaces, volume, locking the screen, logging out, and so on. Using the preexisting parts of XFCE or MATE can make a great starting point for those who aren’t sure they will want to use tiling windows, and users can simply revert changes if they want to go back to floating windows.

Just keep in mind that things can get a tad buggy depending on your setup. When I last combined MATE with i3 on Fedora, I got a lot of visual glitches and some crashes here and there. I had initially given up on the idea of using i3 as a window manager for a DE until I saw a video The Linux Cast did where he used it on XFCE with Arch, and I soon explored the rabbit hole of making the combo work on Fedora. I learned in the case of i3 within XFCE that you’ll need to install a few additional dependencies to make a few components work like workspace switching.

Going back to what I said about this solution, this could potentially work with another window manager as well. I know others have attempted this with bspwm instead of i3, and I am somewhat interested in what the results would be if I tried that combination out. I think swapping i3 with bspwm would be more beneficial for those who find i3’s custom syntax a bit restrictive to work with in a config file.

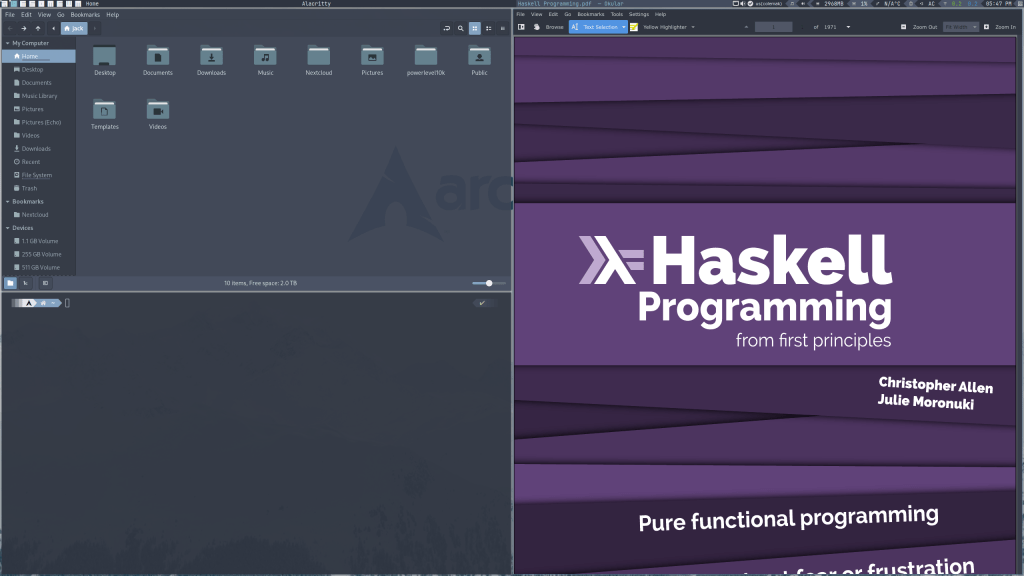

Awesome WM

For regular readers here, you knew this one was coming. Out of all the window managers I’ve used, Awesome is the one I’ve used the longest by far. It’s not even a contest here when it comes to the amount of time I’ve used it as a daily driver. It’s such a comfy, cozy window manager, and it will always hold a special place in my heart.

I initially got started using Awesome WM when I decided to watch DT’s video setting it up out of the box.

This window manager is the main reason I abandoned recreating the macOS workflow on Linux and became a keyboard shortcut ninja.

Unlike many other window managers, this one does come with its own panel and task bar setup out of the box. Granted, it’s rather utilitarian-looking in that default state, but the great advantage is how you can easily deck it out and make it look better than most desktop environments.

For the longest time, I’ve been running a variant of the awesome-copycats with some heavy tweaking and customizations. While I had stopped using my Awesome setup on Fedora due to my monitor setups and configuration, I found it indispensable at home on my Arch machine where my monitors are consistent.

My favorite advantage of Awesome WM that I still hold near and dear is how it handles workspaces out of the box. Other window managers I’ve seen tend to only have visible workspaces when something is visible on it, and then it becomes invisible if nothing is there. By default, Awesome has them visible regardless of that, which is something I do appreciate.

If you happen to do programming in Lua (or you find yourself quite comfortable configuring Neovim?), Awesome is even better, as it is entirely configured in Lua through its default rc.lua file out of the box.

Additionally, as I alluded to earlier, Awesome is the reason I didn’t really use Qtile for very long. I did like Qtile, but I found Awesome so nice to begin with that I didn’t see much of a need to switch. Out of the xorg window managers I’ve tried, Awesome is firmly my favorite.

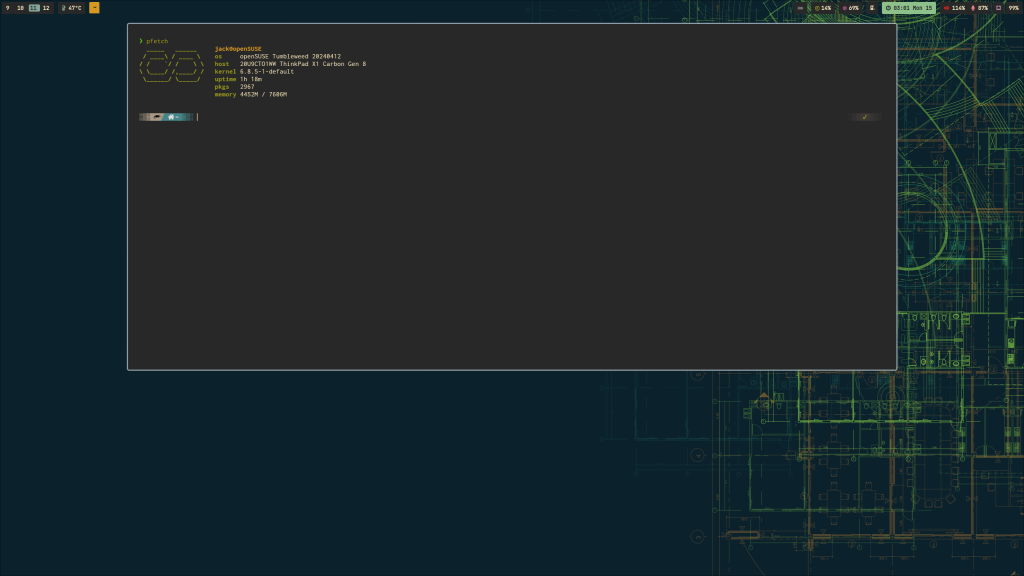

Hyprland

I know somebody out there is prepared to say, “UM AKSHUALLY…” and explain to me how Hyprland is a compositor instead of a window manager because Hyprland uses Wayland instead of xorg. Still, just like when I counted Haiku as a distro, this is my list and I’m still going to count it. Semantics be damned. I have fallen in love with using Hyprland over the past several weeks and don’t see myself going back anytime soon.

Upon snatching the same config from The Linux Cast, I was smitten once I got everything to properly work. Despite a few hiccups with Waybar and workspace management, I finally got things working exactly as I want, which makes my experience feel cozier like it did with Awesome while giving me a lot of graphical eye candy. Oh, did I mention the eye candy? Hyprland is best known for being “a Wayland compositor that doesn’t sacrifice on looks.”

Originally, I was going to write about a few complaints I had regarding the workflow on Hyprland, but I’ve since fixed them and am extremely satisfied with them at the moment. I finally have persistent workspaces just like Awesome WM does instead of active workspaces only (a la i3), I have a working tray on Waybar (You see? I knew it was just something I did wrong!), and I got Pyprland up and running as well to finally try out a great implementation of scratchpads! Hyprland has helped elevate my experience on my openSUSE workstation to the point where I am completely satisfied with my experience and don’t really feel the need to use Fedora any longer.

That’s All!

What did you think of this list? Do you agree or disagree? You’ll probably disagree, but you can still explain why if you would like. What other window managers should I likely try out that offer something these choices don’t? Let me know in the comments! I’d love to hear what you thought.

8 responses to “My Top 3 Tiling Window Managers”

[…] I can’t access the settings and accounts from outside of a GNOME session. Really annoying when Hyprland is my primary compositor right now. […]

LikeLike

[…] is a tiling window manager that runs on macOS and feels right at home for most TWM users on Linux, although their own Github […]

LikeLike

[…] Sudo Science: My Top 3 Tiling Window Managers […]

LikeLike

[…] had to login to my neglected GNOME desktop (I’m pretty sure my Awesome WM setup is broken from lack of use) to start some troubleshooting. After struggling a bit with […]

LikeLike

[…] short, I had a taste of tiling windows a few years ago starting with Awesome WM. After a few years of using it, however, Hyprland became my favorite […]

LikeLike

Great article! I’m new to tiling window managers. I recently installed OMARCHY on a laptop I don’t really need to see what all the hype was about, and am starting to really enjoy it! I just installed awesome and qtile on my debian 13 work laptop alongside xfce so I could give it a try, which is what lead me to your article. I’m really struggling with the basics on awesome and qtile. It took forever to launch a browser! So frustrating! Maybe I”ll install Hyprland instead. Though, I wonder if it’s the OMARCHY customizations I enjoy! Have you tried OMARCHY?

LikeLike

[…] that DT is the reason I ever used AwesomeWM in the first place, I decided it was probably worth the watch. I mean, I don’t use Niri, but why not give it a […]

LikeLike

[…] WM, but I couldn’t find my dot files. Besides, something about simply using Awesome again, as great of a window manager as it is, felt like a form of defeat. It was almost as if I admitted to myself in some way that dwm was too […]

LikeLike